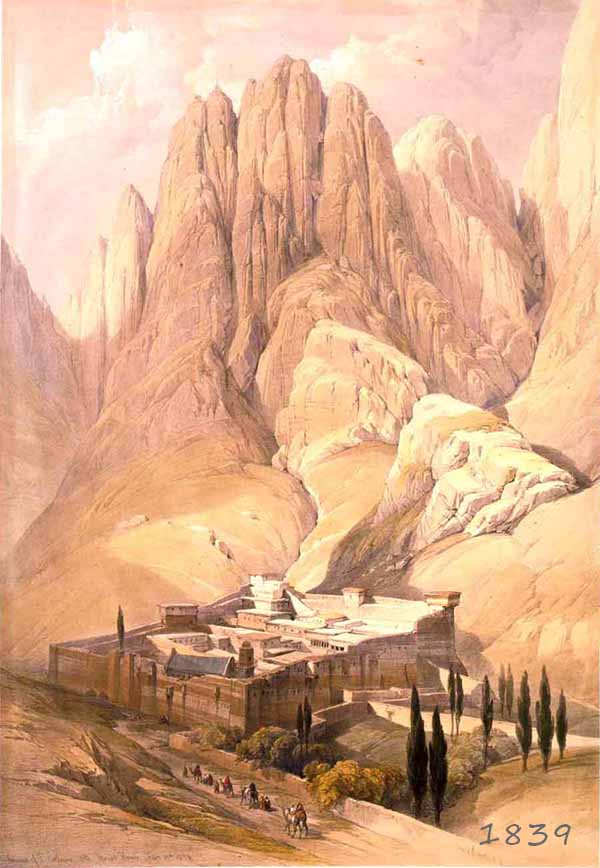

JUSTINIAN FORTRESS

The fortified walls surrounding the monastery enclosure were constructed in the 6th century at the command of the Emperor Justinian. The architect was Stephanus of Aila, which is modern day Eilat. The walls provided the monks with protection from hostile forces that would cross the area, and enshrined within the church built at the site of the Burning Bush. The height of the fortress wall varies from between ten and twenty meters, while its thickness varies from between two and three metres. The north wall of the monastery was badly damaged in 1798, and repaired by French soldiers at the time of Napoleon Bonaparte.

The Entrance

On the west wall one can still see the original entranceway, which was walled up many centuries ago. Above the entranceway is a covered window which allowed those inside the fortress to repel anyone trying to break down the door. Above the original entranceway, a verse from the Psalms is carved in stone, and now only legible in the best light, “This is the gate of the Lord, into which the righteous shall enter.” For centuries, the only entrance into the monastery was through a protected tunnel, or to be drawn up in a basket let down on the north side. The present entrance on the west wall dates from around the year 1862, and consists of three steel-clad doors, the inner door at a right angle to the other two. More recently, a second door was cut into the north wall, to allow visitors to enter directly into the church area during those times when it is open to the public.

Buildings

Justinian’s fortress was built to include the earliest structures built by the hermits of Sinai. The steep incline of the site presented great challenges to the earliest engineers, who had to level an extensive area for the construction of the basilica. The Sinai monastery lacks the large central courtyard that would have been traditional even at that time. The building materials are local and simple – granite, humble timbers, reeds, earthworks – and in keeping with the ascetic nature of the place. Roofs are flat as a rule, and windows are small. The basilica stands out in this complex, constructed as it is of hewn granite stones, and containing within the famous mosaic of the Transfiguration, numerous icons, and other treasures of the monastery.

The monastery catholicon is surrounded by nine chapels and a bell tower. There are a further twelve chapels within the monastery complex. Adjacent to the Tower of Saint Helen is the residence of the Archbishop, the offices of the Secretary, the Synaxis, where members of the community gather to discuss various matters pertaining to the monastery, and the Chapel of the Life-giving Spring. To the west are accommodations for pilgrims, and to the north are administrative offices. To the east are the old bakery and the refectory, and a range of cells. The south wing, completed in 1951, was constructed to house the monastery library, conservation workshops and icon storage rooms, as well as to provide more recent monastic cells.

The Cells

The Sinai monastery was constructed on ground that has a steep incline. For this reason, there is no open central courtyard, and the cells of the monks are scattered throughout the fabric of the building complex. The oldest cells are in an area to the south of the basilica. A range of cells along the east wall date from the fourteenth century, while yet another range of cells along the west wall date from the sixteenth century. They are constructed of humble building materials, using any piece of wood, which was always scarce in the Sinai desert, and often using mud for walls and roofs. Yet these humble materials are very insulated, retaining warmth in the winter, and resisting the heat of the sun in the summer. The newest cells are those along the south wall.

Other Outlying Buildings

The other areas within the fortress walls serve the needs of the monastery in various capacities. In the past, supplies were transported to the monastery with great difficulty, and reached the monastery infrequently. For that reason, many storerooms were needed to keep wheat, oil, and other foodstuffs. The early kitchen area is located in the northeast corner of the monastery, where two old mills are still in place. To the northwest is the office of the Economos, who was responsible for the supplies of the monastery. Pilgrims are given hospitality in this area following the Liturgy on Sundays and feast days. Other offices are ranged along the western wall.

An area to the west of the basilica was used in ancient times to crush olives and extract olive oil. The circular area with its great stone wheel, and the olive press, are still in place.